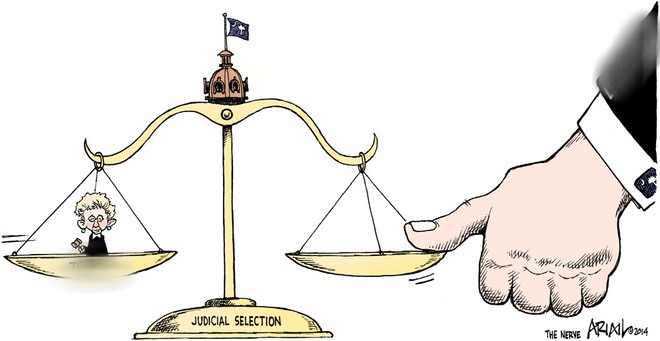

From the New York Law Journal. I like how the author describes it as a, “questionable prosecutorial practice”, not the fraudulent, corrupt and unconstitutional practice it is. The writers missed a good chunk of the Judge Sullivan angle (he was my Judge, Steinberg’s judge and in a mathematically impossible manner, the Judge of numerous other insider trading cases, not unlike Judge Lechner before him in a previous era.

Jonathan Bach and Reed A. Smith

A high-profile insider trading prosecution, currently pending in the Southern District of New York, has yielded the first indications that the tide may have turned against a questionable prosecutorial practice of channeling certain criminal cases around the district’s system of random judicial assignment. In a unanimous order in United States v. Blaszczak, the district’s Assignment Committee has, for the first time, rejected the government’s position that the government properly caused a new case to be assigned to the same judge who had handled a prior, related case, and has directed the clerk to reassign the case to a judge selected at random. Order, June 8, 2017, issued in United States v. Fogel, 1:17-cr-00308. The order is issued in the wake of United States v. Newman, 773 F.3d 458 (2d Cir. 2014), where the Second Circuit went out of its way to criticize the government for channeling cases, although that issue was not even directly before the court. It appears to represent a departure from the Southern District’s previously more tolerant attitude with respect to an increasingly controversial practice. See, e.g., J. Bach and Rachel B. Kane, “Insider Trading Case Raises Concerns About Judicial Assignment,” N.Y.L.J. Sept. 30, 2013 (discussing the case of Michael Steinberg).

The U.S. Attorney’s capacity to avoid random assignment and channel a criminal case to a known judge has turned on a perceived loophole in the district’s local Rules for Division of Business Among Judges (the Rules). Most criminal defendants in the Southern District are randomly assigned to a judge through the system known as “the wheel.” In certain instances, however, the U.S. Attorney’s Office (the Office) will elect to charge a new defendant by “superseding” indictment, effectively joining the new case to a prior case that involves some of the same facts and issues. Under Rule 6(e) of the local Rules, proceeding by superseding indictment ensures that the case will revert to the same judge who handled the case in which an earlier indictment had issued, rather than to a judge assigned at random.

Notably, although the Rules do not define a “superseding” indictment, they suggest that related criminal cases should be directed to a single judge only if the cases are to be jointly tried. Rule 13, which addresses assignment of related cases, deals largely with civil cases. It sets out criteria that a judge should consider in determining whether two or more civil cases are related, and permits a single judge to be assigned to a number of different civil cases, including cases involving different parties and arising at different times, so long as they share a common nexus of facts and issues. With respect to criminal cases, in contrast, Rule 13(b) states that “criminal cases are not treated as related to each other unless a motion is granted for a joint trial.” Thus, Rule 13 appears to presume that criminal cases are inherently individual in nature and will be separately assigned, unless they are so inextricably intertwined as to be essentially a single case. That treatment of related criminal cases broadly comports with Rule 6(e)’s position on superseding indictments, since the conventional use of a “superseding” indictment is to add additional charges or additional defendants for purposes of trial.

Absent a controlling definition of “superseding” indictment, however, prosecutors have operated as if they have two separate and equally defensible choices, with largely unlimited discretion to decide whether a new defendant’s case will be randomly assigned or joined to an earlier case. In some cases the Office proceeds by superseding indictment. In others, where it has an equal option to supersede, it files a new indictment and obtains a judge assigned at random.

Background

The practice of channeling cases by superseding indictment percolated through a series of high-profile insider trading prosecutions, including the prosecution of former SAC Capital executive Michael Steinberg. United States v. Steinberg, 12 Cr. 121. In Steinberg’s case, all defendants under the prior indictment were already out of the picture, having pleaded guilty or been convicted at trial. Thus, there was no possibility of a joint trial as contemplated by Rule 13. Moreover, by superseding the prior indictment, the U.S. Attorney’s Office was channeling the case to a judge who had already ruled in the government’s favor on an unsettled legal issue potentially dispositive of Steinberg’s case. Steinberg’s counsel challenged the Office’s approach, arguing that to “supersede” before a judge who had already ruled in its favor smacked of forum shopping, and that the notion of a “superseding” indictment was, at best, a formalistic contrivance in a case where the original charges had been resolved against all the other defendants. Letter from Barry Berke of Kramer Levin Naftalis and Frankel, April 2, 2013, 12 Cr. 121 (Doc. No. 253).

While Steinberg did not prevail on his challenge, his arguments drew the attention of the New York Counsel of Defense Lawyers (NYCDL), which submitted an amicus letter in his support, and then of the Second Circuit, when it heard the appeals of Todd Newman and Anthony Chiasson, defendants tried under the earlier indictment in Steinberg. Steinberg’s case was not even directly before the Second Circuit in Newman. Nonetheless, at oral argument in Newman, the government faced pointed questions about whether the Office had channeled Steinberg’s case to obtain a litigation advantage. The Newman opinion also went out of its way to discuss Steinberg, noting that the government had superseded in that case only after the district court judge “refused to give the defendants’ requested charge on scienter now at issue on this appeal, and at a time when there was no possibility of a joint trial with the Newman defendants.” 773 F.3d 458, 450 n.5. The circuit’s comments attracted notice not just in the legal press, but as far afield as the Wall Street Journal and The New Yorker magazine. E.g., Jacob Gershman, “Judge Kozinski Faults Prosecutors for ‘Sleazy’ Tactics in Steinberg Case,” Wall Street Journal (Nov. 20, 2015); James B. Stewart, “Some Fear Fallout From Preet Bharara’s Tension With Judges,” N.Y. Times (April 16, 2015) (noting Second Circuit’s criticism of apparent “judge shopping” in Steinberg), Jeffrey Toobin, “The Showman: How U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara struck fear into Wall Street and Albany,” The New Yorker (May 9, 2016) (discussing Second Circuit’s opinion in Newman, including the footnote relating to Steinberg).

‘Blaszczak’

With that background, we turn to Blaszczak and the Assignment Committee’s recent order. On May 24, 2017, the U.S. Attorney unsealed an indictment in Blaszczak charging four defendants with insider trading. The indictment, as styled by the government, purportedly “superseded” an information filed on May 19, 2017 against Jordan Fogel. As in Steinberg, Fogel was already out of the picture. He had pleaded guilty before a magistrate judge to all counts of the information without ever directly appearing before his assigned district judge. Armed with the Second Circuit’s Newman opinion, counsel for two of the defendants (including, coincidentally, the same counsel who represented Michael Steinberg) objected to the Office’s decision to supersede the Fogel information. In a letter to the district judge and Assignment Committee, counsel argued that there was no possibility of a joint trial with Fogel as required for related case treatment under Rule 13, that the indictment was superseding in name only, and that affording the U.S. Attorney’s Office unfettered discretion to proceed either by superseding or original indictment not only created an appearance of impropriety, but implicated concerns of fairness and due process. Letter from Barry Berke of Kramer Levin Naftalis and Frankel, David Esseks, Allen & Overy, May 5, 2017, 1:17-cr-00308 (Doc. No. 28). In addition, counsel observed, while considerations of judicial economy had no role in the assignment of a criminal case under the Rules, there was also no benefit of judicial economy to be gained in Blaszczak, since Fogel had never appeared before the district court judge. Id

In response, the government emphasized that the Rules did not purport to define the term “superseding indictment,” and contended that, to read Rule 13(b)’s definition of “related” criminal cases as a limit on the legitimate use of superseding indictments, would have absurd results. Letter from U.S. Attorney’s Office, June 2, 2017, 1:17-cr-00308 (Doc. No. 35). It would mean, the government argued, that a new defendant could not be added through a superseding indictment unless a motion were first “granted for a joint trial” under Rule 13(b). Id. The government also stressed, that in contrast to Steinberg’s case, there could be no suggestion in Blaszczak that the government had superseded to benefit from a prior legal ruling. It noted that its practice of joining new defendants by superseding indictment was long-standing, had survived prior challenges by defendants, and that, in general, its decision to supersede or not, turned on a unique balancing of a number of case-specific factors. Id. Notably, perhaps, while the government suggested that these case-specific factors would explain seeming inconsistencies in its charging decisions, and belie any inference of improper motive, it did not offer an account of how the factors applied to explain its decision in Blaszczak or any other cases. See id.

The NYCDL also reentered the controversy. It submitted an amicus letter expressing continuing concern with prosecutors’ ability to influence judicial assignment through procedural charging decisions, and with the lack of any neutral governing principle for the government’s choices. Letter of NYCDL, May 30, 2017, 1:17-cr-00308 (Doc. No. 29). “There appears,” wrote the NYCDL, “to be no policy, no articulated rationale, and no consistency governing such choices,” so that “[a] reasonable observer might well conclude that the Government is simply picking and choosing among judges.” Id.

The Assignment Committee’s order was succinct in its rejection of the government’s arguments. As the order states, the Committee “unanimously concludes” that the Blaszczak indictment “does not supersede the information styled United States v. Jordan Fogel, 17-Cr-308” and “the Clerk of the Court is directed to file the Indictment as a new criminal action … and randomly assign the case in accordance with Local Rule 6(b).” Order, June 8, 2017, issued in United States v. Fogel, 1:17-cr-00308. Whether Blaszczak will lead to a change in charging practices at the U.S. Attorney’s Office remains to be seen. In the meantime, the Assignment Committee’s recent order is one of which defense lawyers will want to be aware.

Recent Comments